Written by Melanie Oppenheimer, Professor of History, Flinders University and Australian Red Cross’ Centenary Historian

Background

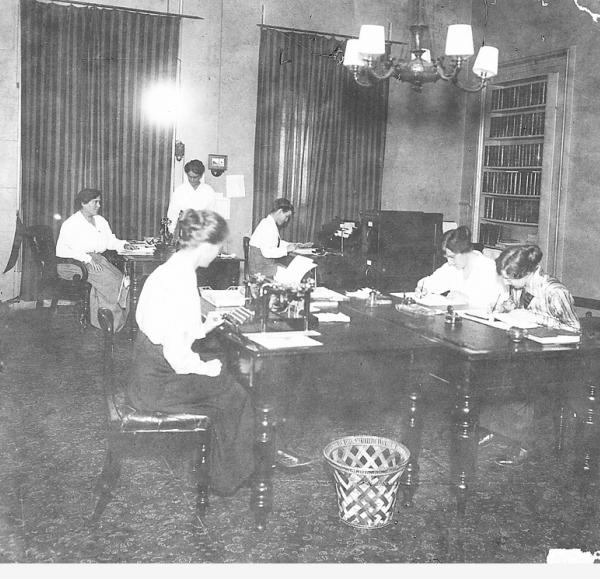

In response to the outbreak of World War I, the Australian Branch of the British Red Cross Society (generally referred to as the Australian Red Cross) was formed on 13 August 1914 in Melbourne. Within days, and encouraged by its President and wife of the Governor-General, Lady Helen Munro Ferguson, State-based Divisions were formed across the country.

In South Australia, the Governor’s wife, Lady Marie Galway, and wife of the mayor, Mrs Simpson, inaugurated the South Australian Division at a large meeting held in the Adelaide Town Hall on 14 August. The headquarters of the South Australian Division and its depot were established at Government House, on North Terrace. The stables were later requisitioned for the packing of soldiers’ comforts.

The work of the Red Cross─to assist the wounded and sick soldiers, his dependents and allied civilians overseas─was sustained by the volunteer work of thousands of members, mostly women, through a branch network that extended across the country. Early South Australian circles (as they were known in this State) established in August 1914 include Glen Osmond, Hindmarsh and St Peters in Adelaide, and Burra and Crystal Brook near Port Pirie. By June 1918, South Australia claimed 369 circles. Throughout the war, industrious members sewed, knitted, baked and raised significant funds for the Australian Red Cross.

Until mid-1915, the Australian Red Cross largely left the administration of its goods and funds overseas to representatives of the British Red Cross in Egypt and London, members of the AIF medical services in Egypt (such as Major James Barrett) or Australian government representatives such as the former Australian Prime Minister and now Australian High Commissioner to Britain, Sir George Reid.[1]

Establishment of Australian Red Cross Wounded and Missing Enquiry Bureaux

In response to the Gallipoli campaign, the Australian Red Cross decided to appoint two Red Cross Commissioners to co-ordinate its efforts overseas. Adrian Knox KC from Sydney and Norman Brookes, a former Wimbledon tennis champion, from Melbourne were selected.

As Australian Red Cross Commissioners, in military uniform and with honorary rank, the men were to administer monies and goods to the military medical facilities and liaise with the parent organisation, the British Red Cross Society, in establishing a Bureau of Inquiry for missing and wounded Australian soldiers. The Commissioners were directly responsible to the Central Council of Australian Red Cross chaired by Lady Helen in Melbourne.

During the war upwards of fifty men served as Australian Red Cross Commissioners. All Commissioners travelled to Egypt and Europe at their own expense and received no remuneration for their Red Cross war work. Commissioners from South Australia included Edwyn ‘Jim’ Hayward, director of Adelaide department store John Martin & Co. His distinguished career included a posting to Malta during the Gallipoli campaign. Later, in France as a Red Cross Commissioner, he was mentioned in despatches and received a CBE and OBE for his war services.

Keen to assist the war effort and encouraged by family friend Norman Brookes, now Red Cross Commissioner, Vera Deakin, daughter of former Australian Prime Minister Alfred Deakin, arrived in Egypt in October 1915 with her friend Winifred Johnson. They began volunteering with the newly established Wounded and Missing Bureau. With the evacuation of Gallipoli and the transfer of the AIF to France, the Australian Red Cross relocated the Bureau to London. As Secretary and Assistant Secretary respectively, Vera Deakin and Winifred Johnson were assisted by a team of volunteers and paid staff for the next two and a half years. The Bureau was expanded to include a Prisoners of War Department run by Melbourne born Miss Elizabeth Chomley. The Cairo Enquiry Bureau was closed on 22 July 1919 and the London Office followed later that year.

These records (around 32 000 cases) were returned to Australia and later deposited with the Australian War Memorial [1DRL/0428]. They have been digitised and are available online.

The records complement and enhance but do not replicate the records of the South Australian Information Bureau held at the State Library of South Australia.

The Searchers

Working closely with the British Red Cross, the task of the Australian Red Cross volunteer searcher was to piece together the fate of a soldier through compiling information from eyewitnesses to the extreme chaos of battle, and relaying that information back to the enquirer. Their work came in rushes especially after the spring offensives on the Western Front in 1916, 1917 and 1918. The volume of the task at hand, the catastrophic loses on the Somme, then Passchendaele, Ypres and Messines and finally at Villers Bretonneaux reverberated through Red Cross as volunteers struggled to deal with the flood of requests from distressed relatives and friends. It was an emotionally draining and heart-wrenching job for everyone involved.

The work of the Australian Red Cross searchers was an essential part of the Red Cross Information Bureau. Most were trained lawyers for, as Searcher Frank E. Pulsford from NSW declared: ‘A searcher must understand a good deal of those rules of evidence which obtain in a Court of Law’. He went on:

‘In most cases the witness does not tell his story at all, or gives only a few points of it; the Searcher must usually by skilful cross-examination, exact the real truth in the form in which it is of value as evidence’.[2]

Searchers seeking information on the wounded and ill soldiers encountered problems as they navigated their way around the thousands of hospitals and camps (there were 1 400 hospitals in Great Britain and Ireland alone). The work was also monotonous, with only ‘five men in every hundred’ spoken to having any information of value.

When an eyewitness to a specific case was located, the searchers set about securing as accurate and detailed responses as possible to verify the circumstances of a soldier’s death or injury or whereabouts. The questions were:-

- eyewitness, how far away, if not how does he know about it

- particulars of unit

- locality of casualty

- time of day

- by what missile hit (shell, bullet etc)

- where hit (what part of the body)

- what was he doing at the time

- how long did he live

- if dead or wounded was he conscious after being hit – was he carried away and by whom, and if possible where was he taken to, where did he die

- where was he buried

- was a cross erected

- description – any Christian name or nickname; any description as to marked characteristics, height, complexion etc; what part of Australia did he come from, how was he employed in Australia; by what boat and when did he come over.[3]

Australian State-based Bureaux

Due in no doubt to the influence of Adrian Knox, described by Sir Josiah Symon as ‘the Leader of the Sydney Bar’, the first State Bureau to be established was in New South Wales in July 1915. Bureaux in Melbourne, Perth, Brisbane and Hobart soon followed led by members of the legal fraternity and Associations in each State.

Each Bureaux dealt with soldiers who enlisted in their own State. However, there was close communication between all Bureaux who assisted enquiries of soldiers enlisted elsewhere including New Zealand.

The work of the Bureaux mirrored the battles of the war. With heavy fighting around the Somme in mid-1916, for example, enquiries increased enormously, with around 100 per day received in the London office from Bureaux across Australia. There were significant problems for Australian Red Cross in terms of delays with cables (six to twelve days in transition) including congestion and sometimes mutilation of cables, delays in the naming of hospitals; and not providing enough specific detailed information.

The South Australian Information Bureau

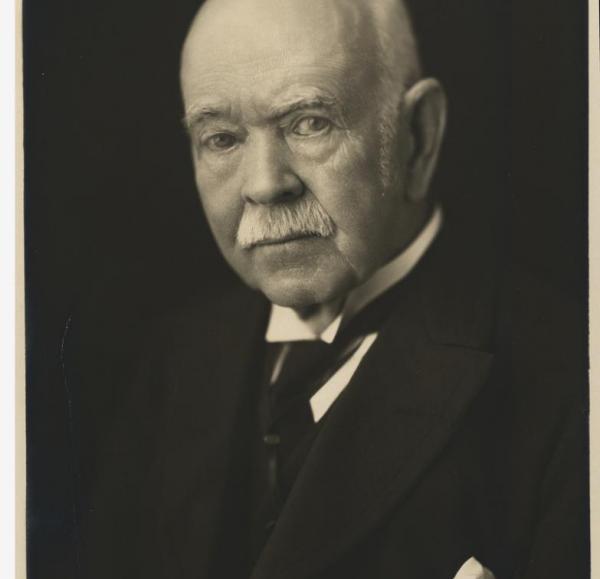

Encouraged by the State Division of Australian Red Cross and with the support of the Council of the South Australian Law Society, Sir Josiah Symon, KCMG, KC led the push to create the South Australian Information Bureau. In mid-October 1915, after communication with Langer Owen in New South Wales about how to actually ‘create’ a Bureau, Symon gained approval from the South Australian Division to establish the Information Bureau.

On 24 November, Symon was unanimously elected as a member of the General Committee of the South Australian Division. An executive committee was formed with Symon as Chairman and Charles ‘Chas’ Edmunds, Secretary of the Law Society, as Honorary Secretary. Other committee members, all Adelaide lawyers, included Mr T. Slaney Poole, Mr George McEwin, Mr J. M. Napier and Mr R. W. Bennett. Miss Florence Saunders became the Office Manager.

The proposed work of the Information Bureau was particularly relevant to lawyers, Symon suggested, because ‘for one reason their trained minds and experience in investigation will be of great advantage in investigating and dealing with the enquiries’.[4] It was also a chance for members of the profession who could not volunteer for active service to ‘volunteer to do this work for the public’ that would be ‘a very gracious, acceptable, and patriotic act of service’.[5]

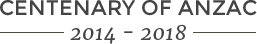

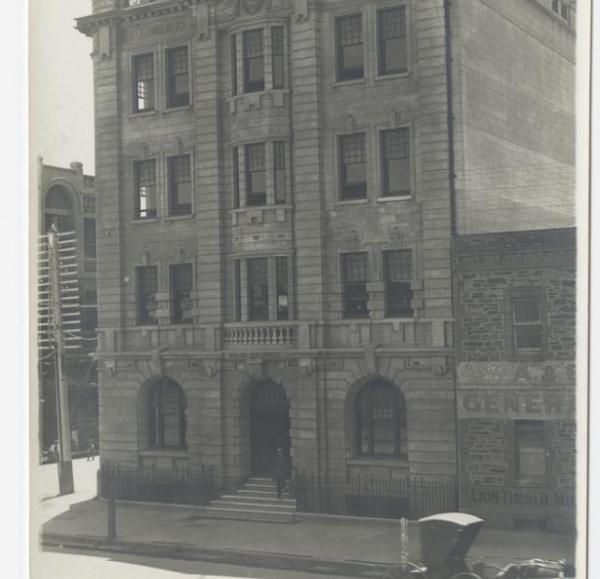

The South Australian Information Bureau was formally established in December 1915 and opened its doors for business on 6 January 1916. Rooms in the newly built Verco Buildings on North Terrace, a stunning example of modernity, were donated free of charge by Dr William Verco (also a member of the South Australian Red Cross General Committee). South Australians were invited to write or call into the Bureau, generally open to the public between 2.30 and 5.00 p.m.

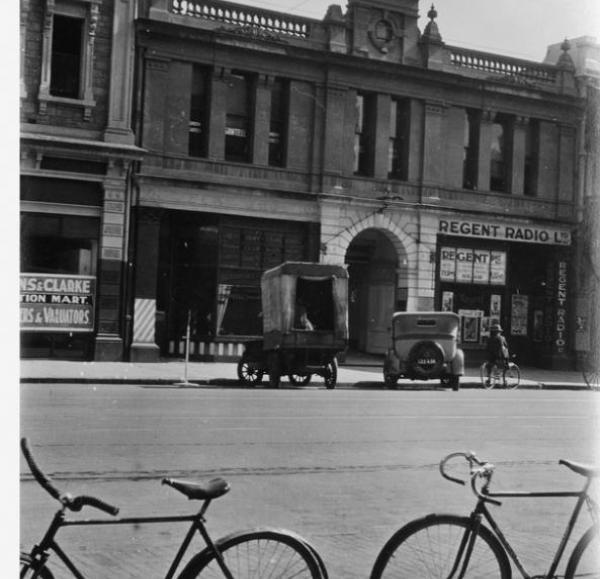

The Information Bureau remained in the Verco Buildings for two and a half years until a move in June 1918 to a large space in the Darling Buildings in Franklin Street (with the financial support of Mr Barr Smith). The Bureau re-located once more in 1919 to two rooms in Queens Hall, Grenfell Street until it closed its doors in January 1920.

Local businesses threw their weight behind the initiative. Messrs Davis, Browne and Co and John Martin and Co assisted with furnishings. The Eastern Extension Cable Company provided cable concessions.

Day to day activities

It was only through Red Cross networks that desperate relatives could find out vital information and what had happened to their loved ones, first at Gallipoli and later on the Western Front. Relatives and friends who were concerned about a soldier attended the Bureau in person or wrote a letter. With the mornings full with the vast array of administrative and organisational tasks undertaken by Bureau volunteers, personal interviews with concerned inquirers were held each afternoon with legal representatives.

When an inquiry was received, either by letter or personal visit, a card was opened ‘and carefully filed in packet form under an index also noted on the cards. This packet would contain a complete record of every step taken, and all information obtained relative to the particular soldier’ in duplicate.[6] The index card system was continually updated with official lists issued by military authorities. As soon as any information was received, it would be duly forwarded to the enquirer.

The scope of the Bureau work extended from general enquiries to requests for details of graves and burial sites.[7] If possible, photographs of graves, remittance for monies for POWs, as well as enquiries for men enlisted in British forces, were all handled by the Bureaux.

The enquiry work of the Bureau fell under six main categories:

- soldiers officially wounded or ill;

- soldiers officially seriously, severely or dangerously wounded or ill;

- soldiers missing or wounded and missing;

- soldiers killed in action;

- special cases; and

- prisoners of war.

Depending on the enquiry, the information to hand, and the relevant category within which the enquiry fell, and the financial capacity of the enquirer, the Bureau responded accordingly. If the £1 cost for a cablegram and reply was too prohibitive for the enquirer, the Red Cross covered the costs. No other fees of any kind were charged to enquirers.

In the first six months of operation, from 6 January to 31 December 1916, the South Australian Bureau dispatched 396 cables and 3 031 letters. A card index system included 260 casualties and 34 returned soldiers, with 1 704 packets filed. By 1919, a total of 5 334 cables and 19 147 letters were dispatched, with 7 910 packets filed.[8]

The Enquirers

The enquirers seeking information through the South Australian Information Bureau included family members particularly mothers and sisters, wives, and female friends. Families were officially notified that their loved ones were wounded or missing and then nothing more. After a couple of weeks of waiting, they then sought the assistance of the Red Cross Information Bureau (See case study of the Alderson family below).

There are also examples of deserted wives finding husbands through the casualty lists published in the newspapers (for example packets 0780 and 1160). A number of female friends sought information independently of families. Perhaps in these cases, there was ‘an understanding’ of which the parents had no knowledge (for example packet 1520).

Families were relieved when the Red Cross confirmed that the soldier has been captured and was a Prisoner of War (POW). Soldiers wrote of receiving Red Cross parcels and being in good health.

The Bureau also worked hard to find information on details about a soldier’s death and especially the exact location of the grave.

South Australian Information Bureau Personnel[9]

Throughout the war a number of people volunteered their time to the Bureau. They were either male solicitors (and one female solicitor, Mrs Napier) from the Adelaide legal fraternity or female voluntary workers who completed clerical and administrative duties. The Bureau required a working staff of up to five clerical assistants and as many solicitors as could spare the time during the Bureau’s opening hours. They nominated regular shifts throughout the war.

From the Annual Reports of the Law Society of South Australia, however, it appears that only a small core group of solicitors actually volunteered their time, and that the Bureau did not receive ‘either the voluntary or financial support to the degree which was expected’.[10] The Honorary Secretary, Charles Edmunds, his sister Mrs Olive Croft and Miss Florence Saunders gave tireless service and were the key volunteers throughout the war.

The following lists from December 1917 give us an idea of who worked closely with the Information Bureau:

Solicitors:

- Mr Poole

- Mr Johnstone

- Mr H. W. Uffindell

- Mr C. T. Hargarve Jnr

- Mrs Napier

- Mr H. Solomon

- Mr E. H. Limbert

- Mr P. Stow

- Mr A. H. Atkinson or Mr Ligertwood (from Mr R. W. Bennett’s Office)

- Messrs Gunson

- Mr Mortimer,

- Mr Giles

- Mr Hicks

- Mr Dawe

- Messrs Bright & Bright

- Mr E. Benham

- Mr Kelly

- Mr Brown

Voluntary Workers (female):

- Mrs Olive Croft

- Mrs Friedericks

- Mrs Priestley

- Miss Judell

- Miss Le Messurier

- Miss Symon (1918)

- Miss Florence Saunders

Typists:

- Miss Messent

- Miss Hart

Mrs Olive Croft

A stalwart volunteer through the war years, Olive was a sister of Charles Edmunds, and worked alongside her brother in the Bureau.

Miss Florence Saunders

Daughter of A. T. and Helen Saunders, Florence was one of the tireless voluntary workers at the Information Bureau. She used her considerable secretarial skills to good effect and ‘rendered exceptionally fine service in a quiet and unostentatious way’.[11] Florence was awarded an MBE for her war work in 1920. When the Bureau closed in 1920, she was offered the position of Assistant Secretary to the Division at Government House.

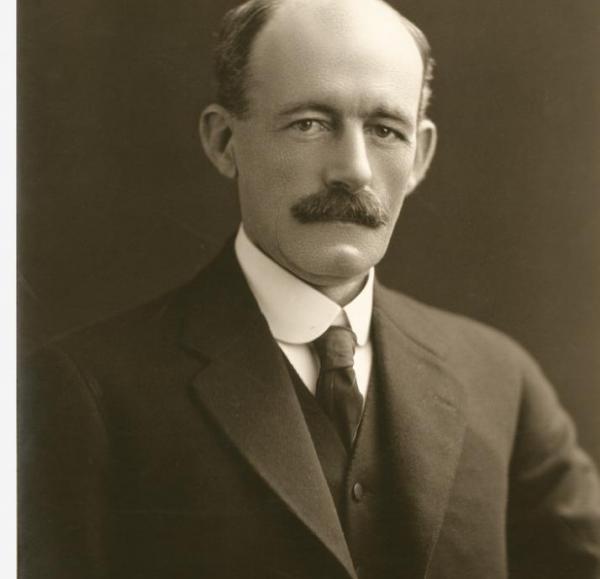

Charles Edmunds

Honorary secretary of the South Australian Information Bureau, Charles lived at Aldgate and was a long time warden at the Church of the Epiphany, Crafers. He was Secretary of the Law Society during World War One, and was one of the main volunteers at the Bureau. His association with Red Cross continued after the war including holding the position of chairman of the South Australian Division of Australian Red Cross.

Case study Packet 102. Sergeant L. R. Alderson, 16th Battalion, No 1119

Mr William Henry Alderson (and wife Annie), from Solomontown (worked for the South Australian Railways), first approaches the Bureau on 29 February 1916 in person to inquire after his son, Sergeant Lancelot Alderson. His Battalion left Egypt on 10 April 1915. A cablegram was received on 10 June 1915, ‘regret son Sergeant LR Alderson wounded, not reported serious, no other particulars available, will immediately advise anything further’; Mr Alderson writes for more information to both Minister for Defence and Base Records in Melbourne. He receives a response, dated 5 August, saying no further information from Acting Secretary, Trumble on behalf of the Minister of Defence; then 6 August from Base Records stating ‘not reported as seriously wounded…it is regretted that the hospital in which he is located is not at present known here’. The Alderson family obviously write to their local representative in Federal parliament, Senator J. Newland, in October asking for him to advocate on their behalf – NOTHING. Again on 6 December, Mr Alderson writes to Base Records Office in Melbourne, once again he gets no answers – the matter remains ‘under investigation’. Then on 15 February 1916, ‘regret to inform you 1119 Sergeant LR Alderson, 16th Batt reported wounded now officially reported wounded and missing second May’.

Mr Alderson relates all this to a member of the Bureau on 29 February 1916. Further he relates that his son was wounded on 2 May 1915 and placed on a hospital ship but that all trace of him was lost. Two letters from his mother had been returned from the Dead Letter Office marked ‘wounded’ in pencil and then struck through with ‘killed in action’. To complicate matters, his niece has written to say her husband, Norman Livesay, saw Lance in a hospital in Egypt but nothing has come of it. (Livesay was to die in action, at Pozieres, September 1916, no known grave.) Mr Alderson leaves 25 shillings to help with cable costs.

On 13 March 1916, Red Cross Commissioners cable to Red Cross Information Bureau Adelaide – “1119 Alderson unofficially believed died of wounds”. Two days later, the Red Cross Information Bureau writes with the news to Mr Alderson.

On 18 March, WH Alderson writes to Mr Edmunds, ‘I sincerely thank you and your Society, for being able to do so promptly obtain information respecting my son, although not of a promising nature, but naturally that is what we are prepared for. Hope the particulars sent your Commissioners in Egypt will lead to definite news one way or the other’.

One month later, on 19 April, further news confirming the fate of Lance Alderson was given to the Alderson family with the advice ‘We deem it as well to warn you that these statements by other soldiers must be received with a good deal of caution, even although they are carefully tested’.

In October 1916, the Red Cross once again send more information to Mr Alderson – with two more eyewitness accounts of Lance’s last moments. Edmunds writes ‘We very much regret that we have never been able to gain any definite information concerning your son after he left the dressing station, but our Commissioners inform us that it is almost impossible, in cases where men are reported to have died on Hospital Ships to obtain any details of their death or place of burial unless they are officially reported to have been buried at sea…from private sources our Commissioners have gathered that unless a man died after the ship docked he is generally buried at Sea’.

Alderson was officially certified as Killed in Action, 2 May 1915 in August 1916. His family was notified accordingly. On 30 October 1916, Mr Alderson writes to Edmunds ‘I am very grateful to your Society and the Commissioners for the valuable information obtained, and fully realize the difficulty there must be in tracing a large number of cases of men wounded and missing. He is now officially reported killed by the Military Office, and a few of his belongings found, have been returned to me’.

[1] For a detailed history of Australian Red Cross, see Melanie Oppenheimer, The Power of Humanity: 100 Years of Australian Red Cross (Sydney: HarperCollins, 2014).

[2] ‘The Australian Red Cross Wounded and Missing Enquiry Bureau’, undated, c. 1917, SRG 76/31.

[3] South Australian Red Cross Information Bureau, SRG 76, series 32-33.

[4] JH Symon, ‘Australian Red Cross Society Information Bureau, To the members of the legal profession’, 26 October 1915, SLSA, SRG 76, series 32.

[5] Ibid.

[6] ‘Red Cross Information Bureau’, Red Cross in South Australia, Part 2, Between the Wars 1918-1938, researched and compiled by Margaret N. Ewens, p. 1. SLSA, SRG 770/39/2.

[7] The Red Cross was closely involved with compiling lists of burial sites in France and Gallipoli at the end of the war, as well as facilitating the 7 543 inquiries for possible burial sites between relatives in Australia and the Australian military (Captain Spedding, Australian Corps Burial Officer), Captain Mills, the Australian officer attached to the British Military Commission in Germany, and Colonel Hughes working in Turkey. ARCS, 6th Annual Report, 1920, p. 11.

[8] Red Cross Information Bureau, SLSA, SRG 76/22.

[9] Information from SLSA, SRG 76/22.

[10] Law Society of South Australia Inc and Australian Red Cross Information Bureau, SA Division, Annual Report and Balance Sheet, 1917, pp. 6-7.

[11] Chronicle (Adelaide), 23 October 1920, p. 38.